CHAPTER 9

THE CENTRAL TRIBUNAL & THE HOME OFFICE SCHEME

Satan himself is transformed into an angel of light.

2 Corinthians XI, 14.

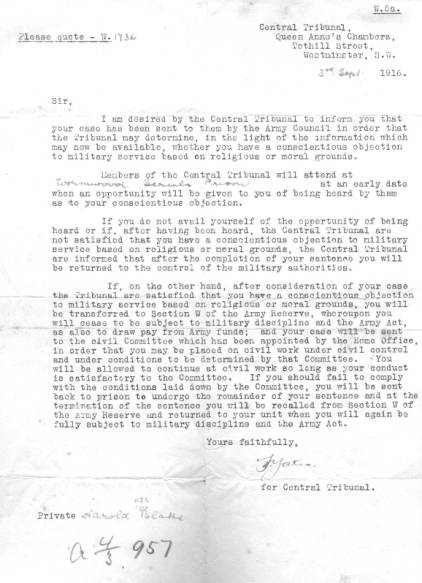

One morning during my progression through stage 2 of my first sentence, an officer handed me the document here reproduced, from the Central Tribunal. It will be noted that it is dated two days prior to my court-martial, but I did not receive it until the end of October 1916.

I read the letter more or less with indifference, but having done so, the chief impression left in my mind was that of outrage. When I had requested leave to appear before the Central Tribunal, I had been refused and had come to the conclusion that there was nothing more to say. Since I had already established conscientious objection to the satisfaction of the tribunal, what new information was there that the Central Tribunal could now want to hear? It was adding insult to injury. Furthermore at this time I was in considerable doubt as to whether I had done the right thing in appealing to the tribunals at all. All along I had been of the view that a body of men was not fit or adequate to judge matters of conscience, but now a further point was concerning me. If we take a matter before an umpire for adjudication, of course we hold our opponent to the decision if it goes in our favour. Therefore he has every right to expect us to honourably abide by the decision if it goes against us. But I had decided that I was not going to be a soldier, before I asked the tribunal to consider the matter. Any decision of theirs either for or against was therefore superfluous. Jesus provides help when we are brought before kings and governors for his sake, but he does not tell us to go with our adversary of our own volition.

By way of digression, I might here say that this question of appealing or not appealing perplexed me for many years, long after the war was over and always, a satisfactory solution baffled and eluded me. The point I reached and at which I stuck, was the conclusion that if I were in the circumstances again, I would write to the authorities on receiving the ‘yellow paper’ explaining my conscientious objection and decline the right of appeal because it is a decided issue in my mind. But I recognised that this conclusion was not fully satisfactory and could not take upon myself the responsibility of advising another to adopt it. When compiling these records, I unexpectedly made further progress on this matter. When studying the quotation at the head of Chapter 4, I wondered why ‘and the Gentiles’? Of course! One does not go before tribunals to obtain justice, that is recognised as an improbability. But God has ordained that the rulers of this world will be called to account when they appear before his last great tribunal and their injustice, when having sat on the judgement of others, will most surely prove to be a testimony against them.

But to return to the document under consideration, it showed that the Central Tribunal had decided against offering absolute exemption. As that was my single requirement, it was obvious as far as I was concerned, that nothing was to be gained by their deliberations. I could not accept any condition that involved me in entering into agreement with the ruling authorities, for to do so would fetter my hands. I realised also that the State would never surrender the right to command the services of its citizens to maintain it in being, for to do so would inevitably undermine its very foundation, especially in such circumstances as arose in 1914 - 1918. Nevertheless this did not deter me from insistence on absolute exemption and refusing any substitute that involves an alternative service. It merely demonstrated to me the irreconcilability in the controversy between Christ and Satan.

I also concluded from the first paragraph that the army was desirous of ridding itself of the embarrassment of COs in its ranks and was beginning to realise that it could achieve nothing by a policy that attempted coercion against firm conviction. That was the only piece of satisfaction to be drawn from the document, yet such is the indomitable woodenness of the military mind, the last two paragraphs abound with threats of further coercive measures. That the COs name would still be included in the list of the army reserve is a statement of incomprehensible imbecility. Were these people totally incapable of grasping that we were asking to be excluded from the army, that we refused to be branded as the property of Caesar and stamped with his image and superscription? However that fundamental blunder served to open the eyes of many to the traps and pitfalls with which the Home Office Scheme abounded.

In due course I was marshalled before the Central Tribunal, which commenced with the Chairman (Sir Donald McLean) asking me questions regarding the grounds of my objection and my experiences before the other tribunals. I started answering these, but was suddenly overcome by the a feeling of the utter futility of it all which swept over me, and I burst out, “Pardon me, but I think you need not waste any more of your time on my case, because I shall refuse the Home Office Scheme even if it is offered to me.” In spite of this, the three members of the tribunal carried through the farce and having made my protest, I assisted them in a respectful and courteous manner.

Several days later about a dozen of us were paraded to the Governor’s office. Outside this emporium we were lined up and the warder in charge read out the set of conditions concerning the carrying out of work on the Home Office Scheme. These were so iniquitous that I immediately rejected them as unworthy of consideration. In addition to those foreshadowed in the above-mentioned letter, I clearly remember one that bound the signatory to abstain from propaganda. To most that would appear innocent enough, but consider where Jeremiah would have stood if he had agreed with the King of Judah to such a condition. How could he have delivered the apparently unpatriotic message that God required of him? And what is the promulgation in wartime of Jesus’ truth, but propaganda against the State.

Evidently the authorities had no doubts that we would eagerly embrace this opportunity of escaping prison life, for without even asking if we agreed, a warder commenced measuring us for fitting the clothes (or should one say the uniform of Section W of the army reserve). I believe I was the first to refuse acceptance of this insulting attempt at subversion and when the officer essayed to put the tape around me, I told him he was merely wasting his time.

It seemed to be official policy to rob us of the moral support of others of like mind. Therefore we were sent into the Governor’s office one at a time in alphabetic order, hence I went first. When I entered, the Governor dipped his pen in the ink and offered it to me with one hand while with the other indicating a place on the paper on the desk and said, “Sign there.” I made no effort to take the pen, but looked at him steadily and replied, “No sir, I can’t sign it.” The Governor was taken completely aback and looked at me as if he could not believe his ears, or thought I had taken leave of my senses. After a pause to recover himself, he voiced his astonishment by saying, “But you realise it’s your only chance of getting out of prison?” To his query I replied, “Well sir, I’ll take the risk.” To this he quickly retorted, “There’s no risk about it at all. It’s a dead certainty that if you don’t sign, you’ll stay here.” Seeing some humour in the situation I answered, “Very well sir, then I’ll take the dead certainty,” and being dismissed, I left his office to resume my place in the line.

Two of the original seven accepted the scheme. Shortly after, we other five were informed that our sentences had been commuted from six months to 112 days. I have no means of understanding why. Supposing no remission marks had been earned, this would bring our release date to Christmas Day, but as we all earned full remission, we were actually discharged on December 8th 1916.

Although this event took place on the day mentioned, I almost suffered a postponement. On the preceding evening when returning to our cells from the workshop, as I turned to enter my cell, with exuberant spirits occasioned by the prospect of release, I whispered to the man behind me, “Good-bye, I’m going out tomorrow.” There was no pause in my movements as I entered and closed the door, which was designed to fasten and lock automatically as it closed, but I had not time to remove my cap before a key sounded in the lock and an officer entered, “What do you mean by talking to that man?” he demanded. I made no reply and the warder continued, “You’ll see the Governor in the morning.” That may or not have been an idle threat, but if it had taken place it would have meant the usual ‘bread and water’. My number was in fact placed ‘on report’, but as the time for seeing the Governor was usually about 10 o’clock, they would have found that the order for discharge had taken effect first and the bird had flown.

As is often the case, the recollection of one incident brings in its train, the recalling of another. Hence one from a few weeks earlier, which has some features in common, for instance it also occurred on our return from the workshop. To understand the matter, the reader must know something of the construction of cell doors. These are built on a timber frame of considerable thickness and faced on both sides with iron sheet, the whole being bound together by numerous bolts. The only handle is on the outside and at Wormwood Scrubs it is merely for the purpose of pulling the door to. The locks are double locking, the second turn of the key shooting the spring loaded bolt further out. When the door is unlocked and opened, a spring catch prevents the bolt from re-shooting. When the door is closed again a pin engages with the doorpost and on being pressed in, it releases the bolt so that the door locks automatically. On the occasion in question, when I reached my cell I found that the lock bolt was protruding and consequently I could not close the door. So I closed it as far as possible, deciding to leave it at that, as the warders would be round with supper shortly and the door lock would then be rectified. Indeed there was nothing I could do, I certainly could not venture out of my cell. Shortly I heard the jingle of keys and turning round came face to face with an irate warder, “Why didn’t you shut your door?” he stormed. “I couldn’t, the lock prevented me” I replied, pointing to the protruding bolt. “What did you want to tamper with it for?” “I found it like that.” “If you get messing about with it again, I’ll report you.” I began to suspect that the whole business had been engineered and I felt the hot blood rising in revolt at his deliberate suggestion that I was lying, but in such an atmosphere of suspicion, it is only to be expected. So I bit my lip and remained silent.

It was the same warder who figured in both scenes and that is an added reason why I think he was so keen to put me on report on the occasion prior to my release.

Whose Image and Superscription?

The story of a First World War conscientious objector