CHAPTER 6

THE CRIME

My son, if sinners entice thee, consent thou not.

Prov I, 10.

The episode to which I now come occurred on August 30th 1916 shortly after the medical examination. It consisted of an escorted visit to the Mobilisation Stores with the object of fitting me for uniform. My escort was an elderly soldier who talked to me on the way to the stores like a father giving advice to a son and in all probability had been instructed to win me by the use of this approach. He told me that he hoped I should not refuse to do as I was asked, not ‘ordered’ I noticed, as things would be very hard for me if I took that course, I might even be shot. If I were cooperative they would never send me abroad, but would put me to some soft job such as sweeping up the barrack yard. I was attentive but silent and we arrived at the stores while he was still pursuing his soft-tongued attempts at persuasion, while in my mind had arisen the picture of the Flatterer, as portrayed in John Bunyon’s Pilgrim’s Progress.

I was asked my boot size and then directed to remove one. This I did, but when required to put on an army boot, I quietly but firmly refused. My fatherly escort immediately shed his sheep’s clothing and displayed himself the wolf he really was by vehement foul-mouthed cursing and abuse, being ably assisted in his tirade by the accompaniment of six or seven soldiers who were in the stores. I saw that these were the cowardly bullying tyrants, selected by the army to terrorise the new recruit. The storm was so sudden and furious that I was taken aback and showed some small emotion of fear, but I quickly recovered myself and remained undauntingly facing them without flinching. Then commenced a period of rough handling, while the soldiers forced on boots and other articles of army dress. Having satisfied themselves that they had effected some sort of fit, they turned their attention to packing a kit bag.

The next proceeding was a typical example of army bullying, the like of which was practised not merely upon COs, but also upon unfortunate young recruits. Two soldiers each seized an arm and held it outstretched horizontally, while the heavy kit bag was hung on my back with the cord pressing hard upon my throat. The tunic, trousers, overcoat and boots were thrown over my arms. Loaded in this manner, I was dragged and pushed back to the guardroom, a distance of about two hundred yards, by the two soldiers who held my arms and pushed from behind by a third. The pressure of the kit bag cord round my throat was causing suffocation and as I felt consciousness slipping from me, I managed to struggle one arm free. By inserting a finger under the cord, I was able to help my respiration, but in doing so I stumbled and fell. While on the ground I was treated to a vigorous volley of kicking from heavy army boots aimed at whatever part of my anatomy presented the best target, all this reinforced by the inevitable storm of foul abuse. Struggling to my feet, I was promptly seized again and propelled as before, but was still able to retain my finger under the kit bag cord. Finally I was thrust into the guard room, the door being slammed and locked behind me.

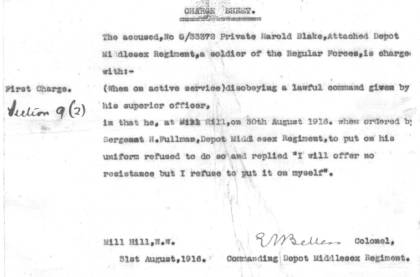

While telling my story to the other COs in the guardroom, the key was heard turning in the lock and the door thrown open, disclosing the figure of the Sergeant of the Guard in the doorway. He glanced rapidly around and espied the discarded uniform and kit bag just within the door. Fiercely fixing his eyes upon me, he roared in his most imperative manner, “Private Blake, put on your uniform.” I neither moved nor spoke but met the Sergeant’s eye and he fiercely demanded, “Do you understand the seriousness of your action?” “Yes, I decline to put it on, but shall offer no resistance to any action of yours.” “That makes no difference. Do you refuse my order?” “Certainly.” The deathlike stillness of the outer guardroom was broken by a number of smothered exclamations, which disclosed that the guard had been listening with intense interest. The heavy ironclad door closed with a bang, indicating the Sergeant’s wrath at this defiance of his authority before the company under his command. A few minutes later the door opened again and the Salvation Army CO whose name was Aitchisson was quietly ushered in bearing a neatly folded uniform. The absence of kit bag and overcoat was explained by the fact that his conscience was recognised and he was drafted into the Non-Combatant Corps. The objector was immediately followed by the Sergeant of the Guard who asked him if he refused to put his uniform on, received an affirmative reply and then withdrew.

An hour or so later, two sergeants arrived who informed us that they had been sent to put the two of us into uniform. Seizing me first, they rapidly stripped me of all clothing and then commenced to replace it by army dress. The actions were accompanied by voluminous abuse and it was clear to me that they strongly disliked the task that had been assigned to them. One of these sergeants had been sent home from the war front, being wounded in the hand. During the dressing comedy he showed me his badly battered hand and remarked, “I’ve nearly lost my hand fighting for you and now you wont do your bit.” In reply to this I said, “No not for me. I neither ask nor accept such a service from any man.” But the demeanour of the two changed when an element of humour arose. This was occasioned while they were inserting me into the khaki trousers. I was seated on the edge of a plank bed and each soldier seized a leg and then each thrust a foot into the trousers. Then lifting me by the waist belt they endeavoured to shake me into position as one would shake down a sack of coal. To their mystification I did not shake down as expected, which led to further abuse, while I knowing the cause of the obstruction, was ready to explode with secret laughter. Eventually they realised that each had put a foot into the same trouser leg. This led to much merriment from all present, yet there was no derision and the soldiers seemed to understand that there was no personal animosity towards them from the watching COs.

The rest of the dressing process was carried out without further abuse and to the accompaniment of quite friendly conversation. When finished, I asked the sergeants to shake hands as a sign of no animosity, to which they readily agreed, which made me feel much better. Aitchisson was then stripped and dressed in quite an amicable atmosphere and his was the last case of forcible dressing carried out at Mill Hill Barracks.

A further amusing episode occurred a few days later. COs were no longer taken to the Mobilisation Stores to be fitted, but a uniform was kept in the outer guardroom. Simons, scarcely more than five feet tall, was called, shown the uniform and ordered to put it on. After he refused, Runham-Brown who was well over six feet tall, was similarly called, shown the same uniform, ordered to put it on and he likewise refused. Afterwards we enjoyed much hilarity imagining the result if Runham-Brown had attempted to put it on, supposing the uniform was sized to fit Simons.

We were all charged with the crime of disobeying a lawful command given by a superior officer and the next break in the monotony of those days was occasioned by a medical examination, to ascertain if the accused were in a fit state to face a court-martial. A court-martial to an ordinary soldier is a terrifying and nerve-racking affair. This is recognised by the army in that no less than three separate medical examinations are required of the prisoner. The first is made before the accused is formally charged, the second before the Summary of Evidence and the third on the day of the trial. To me my first examination felt disgusting and obscene, but this feeling gradually wore away and I came to regard these examinations with indifference or even contempt.

After the prisoner has been charged and it has been decided by the Commanding Officer that a court-martial is warranted, he is taken each morning before the Commanding Officer in the orderly room to be remanded. As applied to COs this ceremony seemed to me to be ludicrous. All the prisoners, both soldiers and COs were marched in a single file from the guardroom to the orderly room, with an escort from the guard marching in a parallel single file, each prisoner being opposite his own particular escort. The Commanding Officer sat at his table, while beside him stood the Adjutant. In the corridor outside was the Quartermaster Sergeant acting as Master of Ceremonies. When the ceremony opened, the Quartermaster shouted, “Sergeant A, Private B, escort, quick march, left wheel, halt, right turn, ‘tention.” ‘A’ being the sergeant in charge of the company to which the prisoner is attached and ‘B’ is the prisoner. The called men then fall into line facing the open door of the orderly room and the cap (if he has one) is snatched from the prisoner’s head. The completion of the manoeuvre brings the three men in a row before the Commanding Officer’s table with the door shut. If the prisoner is at all tardy in his movements, he is jostled and pushed by the escort behind. The Adjutant then states the prisoner’s details and the charge. If a minor offence, the witnesses give their evidence and the Commanding Officer either acquits or pronounces sentence, this being either a fine, confined to barracks, or so many days detention in the guardroom. In the cases of COs the Adjutant proceeded thus, “Private B, charged with disobeying a command of his superior officer,” to which the Commanding Officer snapped out, “Remanded.” Should, however, the date of the court-martial be known, he replied, “Court-martial on …,” and the daily pantomime for that CO was then finished. Then it is over to the Quartermaster again, “Right turn, quick mark, right wheel,” thus reversing the previous manoeuvre. Outside the cap is thrust back on the head of the prisoner and the three men return to their places along the walls of the corridor. The Quartermaster shouts the pronouncement, which is written down by the Orderly.

When the COs came to number half a dozen or more, they monopolised an appreciable amount of time in this way. The Commanding Officer thus introduced a method of receiving all the COs en-bloc. From the preceding description it will be easy to imagine the ludicrous spectacle presented by half a dozen COs calmly and casually walking into the Commanding Officer’s presence, with the sergeant at the head and the escort in the rear, stiffly marching in the regulation way, while the irritated Quartermaster snapped out, “Look sharp.” The effect was to make army usages appear ridiculous and the soldiers involved must have felt extremely foolish. Undoubtedly the officers were concerned lest this effect should communicate itself to the rank and file and it was evident that they began to feel uncomfortable at our presence in the army. It began to be the custom among them to blame the tribunals for foisting this embarrassment upon them, conveniently overlooking the fact that it was the Military Representatives on these tribunals who were responsible for the rejection of many appeals.

This entertaining performance at the orderly room, which never seemed to lose its mirth provoking freshness, occurred for me each morning until the last time on September 2nd, when seven of us were informed that we were to be court-martialled on Tuesday September 5th. These seven were Runham-Brown, Ralph Tinkler, Thomas Brownutt, the two Brown brothers, Simons and myself.

On the Sunday, I awoke before dawn and as the blackness of the iron-barred window slowly give place to the glowing sunlight, I wondered at the inevitable way in which darkness melted into light, the warm golden orb of the sun at length chasing away the last lurking shadows. Here I thought is an object lesson demonstrating the immutable purpose of God in the establishment of his glory. I saw in place of the fear and insecurity of my present condition the time when, “they shall sit every man under his vine and under his fig tree, and none shall make him afraid.” As I pondered these things, I felt the dread of all the unknown things, which were to happen to me in the future, slip away into a profound peace of mind and looked forward with calm confidence.

Many of the soldiers who were thrust into the guardroom were immured for some petty offence and expected on the following morning to be fined three days pay, or three days Royal Warrant. As I understand the latter, it seemed to involve the loss of three days pay, plus a further three days forfeited to some authoritative fund.

One morning in the guardroom, I was highly amused when just before being marched to the orderly room, a group of these delinquents sang to the tune of John Brown’s Body,

Our Sergeant Major is one of the forty thieves,

And the Adjutant’s the other thirty-nine.

Whose Image and Superscription?

The story of a First World War conscientious objector