CHAPTER 4

ARREST

Ye shall be brought before governors and kings for my sake, for a testimony against them and the Gentiles.

Matthew X, 18

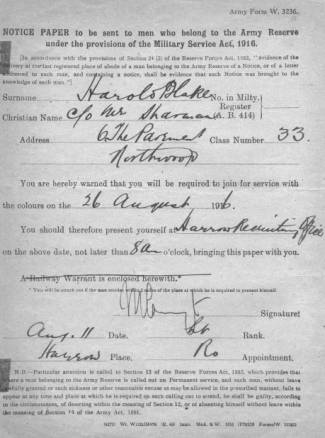

My appeals to the tribunals having achieved nothing in producing a result of a practical nature, it behoved me to await with patience, if not with apprehension, the arrival of my third and last yellow paper. This in due course reached me, in this case from the Middlesex Regiment, requiring me to join the colours for active service by presenting myself at Harrow recruiting office before 8 a.m. on Saturday August 26th. I brought this paper to the notice of my employer, who intimated that he would be glad to retain my services until I was arrested. I pointed out that after the 26th I would technically be a deserter and he would be liable to a fine of £20 for employing me. Although he was over military age, his views on compulsory military service were similar to my own, in consequence he felt somewhat hostile to the military authorities and said he did not mind running the risk. I declined his kind offer stating that I did not feel justified in submitting him to such a danger. Accordingly just before 8 oclock on the morning of the 26th, I left Northwood and travelled by train via London to Luton.

I was not to remain at liberty for long. At about 9 a.m. on August 28th I was received into the arm of the law by the arrival of a policeman. My wife was just starting out to her work and I having a little business to attend to in the town, had prepared myself to accompany her.

Immediately I saw the constable approaching the house, I knew his errand and I hastened to open the door to him myself, in order to circumvent too sudden a shock to my wife or my mother. He confronted me with the query, “Harold Blake?” “Yes I am he.” “Can you give me any reason why you did not report at Harrow on the 26th? And I must warn you that anything you say may be used in evidence against you.” “Because I had no intention of doing so.” “Then I must ask you to come with me.” “Very good! I will be with you in half a minute.” With that I turned to find my mother approaching the door and my wife gone, who previously, had been by my side. My mother asked who was at the door and I told her that the police had sent for me. I requested her to take charge of my belongings, handing her my watch and chain, money, pocket book, knife etc. I then entered the dining room to find my wife sobbing violently and far too much upset to speak. I took her in my arms telling her not to cry, for I was certain I would be all right. Leaving her, I returned to my mother and said to her, “Take care of Amy for me, she is very much upset.” Having then kissed her, I stepped out beside the constable, intimating that I was ready and walked with him to the police station.

Naturally conversation between us was somewhat restrained, but he made an effort to convert me to his way of thinking, for he vouchsafed the information, “If they were all like my family, there would be no COs.” To this I made the equally uncompromising reply, “If they were all like me, there would be no war,” an assertion, the implications of which, seemed to be beyond him.

When we reached the police station, I was taken before the inspector and ordered to empty my pockets. This operation being completed very rapidly, owing to there being nothing to produce beyond three halfpence and a few screws. I was then subjected to the indignity of being searched to see if I had completely complied, a process at the time I very much resented. However I had to submit to a like process on innumerable occasions subsequently. In this case resentment soon gave place to amusement when the inspector regretfully replied, “You beggar! You’re prepared for this.” “Of course I am,” I replied, “I’m not going into this thing with my eyes shut. I have thought out what it means.”

Next I was locked in the police cells until such time as the magistrates would be in attendance. Of all the long hours that burdened me with their wearisome longevity, those few hours were by far the most seemingly unending. The magistrate must have sat before mid-day, but it seemed if he must have tarried until the late afternoon. There was one other prisoner, an army deserter in the proper sense of the expression, with whom I attempted a conversation, but his language was so obscene and his mind so foul, that I soon desisted. My soul shrank back in horror as I speculated whether he were a typical sample of the human beings, amongst whom I was about to be pitch-forked by the leaders of an enlightened community, with the active assistance of the ‘Christian’ church.

During the period of waiting I heard the inspector telephoning to Mill Hill barracks for an escort to be sent to take charge of me. This seemed like a technical illegality, for it amounted to a declaration of guilt before I had been tried and sentenced.

A constable came to the locked gate to ask me whether I would accept the provision provided by the station, or desire a message to be sent to my people, that they should send dinner for me. I decided upon the latter, chiefly because I surmised that an opportunity of seeing me would be welcomed by them.

Eventually the court opened and my fellow prisoner and I were escorted into the dock and the Chief Inspector, who chanced to be a prominent member of the chapel which was the spiritual home of my earlier years, came to inspect us. As soon as he saw me he said contemptuously to the constable on duty, “Another CO?” Taking up the challenge I exclaimed, “The shame is yours.” Yet I felt somewhat elated that it appeared such an easy matter to distinguish a CO from the ordinary offender.

The Court House, Luton

Photo: The Luton

News

As soon as the magistrate had taken his seat on the bench, the full grim humour of the situation became apparent to me. For he was none other than my former Sunday School Superintendent who knew my character and upbringing almost as well as I did myself. Would he refuse to commit me, knowing that my religious convictions absolutely forbade my participating in war? The atmosphere became, for me, electric and I waited with strained attention to see what he would do. The other prisoner disposed of, the constable who had fetched me from home, was called to give evidence of the arrest. The magistrate then said in hurried nervous sentences, without pauses that would allow me an opportunity to answer any of his rapid sequence of questions, “Have you anything to say? You haven’t? No! Well you be fined forty shillings and remanded to await a military escort. We have to do that you know.”

I thought of Pilate attempting to salve his conscience by declaring, “I am innocent of the blood of this just person.” The magistrate’s moral courage had failed and that he was uneasy in his mind over it was shown by his final veiled apology. With a sigh of relieved tension, the strained situation passed and the thought came to me that after all, his was the least enviable position. Indeed I felt genuinely sorry for him. I was following the light of the pillar of fire into the wilderness; he also had seen the light, but had declined its leading. He was a living illustration of the poet’s words: -

Reputation? That’s man’s idol,

Set up against God, the maker of all laws,

Who hath commanded us we should not kill,

And yet we say we must for Reputation!

What honest man can either fear his own,

Or else will hurt another’s reputation?

Fear to do base unworthy things is valour,

If they be done to us, to suffer them is valour too.

Ben Jonson.

With my remark that, I had made all my statements before the tribunals, the court incident closed and the magistrate left the bench, after which we two prisoners were returned to the cells.

The police up to this point had shown no vindictiveness, but for some reason, of which I had no means of knowing why, the constable came to the gate of the cell in a towering rage and said to me, “If I had my way I would shoot you lot.” To this I replied in cool indignation, “Thank you and how much better off would you be?”

The next break in the weary waiting in the cells was the arrival of an escort for my fellow prisoner, who was carried off cursing and swearing volubly. I make no secret of the fact that I preferred his room to his company. His departure was closely followed by the arrival of my wife and younger sister who beheld me behind locks and bars for the first time. My wife was quite calm, but my sister I could see was close to tears. She asked me in an attempt at cheerfulness how I liked it and I replied that it was not too bad, but that no doubt it would get worse as I got further along.

At about 3 o’clock in the afternoon my escort arrived from Mill Hill and the police, having restored my three halfpence, handed me over to their keeping. The escort consisted of a corporal and a private, both of whom treated me with respect, but engaged me little in their conversation. Arriving at the barracks I was taken to the orderly room, where the corporal left me in the sole charge of the private. The clerks took particulars of my police court adventure and when I informed them of the forty-shilling fine, I was greeted with a roar of laughter and the query, “Is that all?” I smiled in reply and responded with, “Isn’t that enough?” Which evoked the reply, “Ah well, it’s a start.” Why the matter should appear funny to them I did not at that time understand, but when in course of time I learned more of army usages, I saw they pictured me as being without pocket money for some weeks. Of course as I had not the slightest intention of accepting army pay, I myself knew that it would not make the smallest difference to my financial circumstances and whether or not the police ever recovered the fine and if so from whom, is to this day unknown to me.

Next I was conducted to the recruiting office where I was subjected to another cross-examination with respect to routine personal details. The clerk having set down my answers on a form, asked me to sign. I asked if I might read it first and when I had satisfied myself that he had made no mistakes, I enquired, “What do I commit to if I sign?” To this he answered, “Nothing whatever, except that your answers are correct.” But preceding the dotted line where he indicated that I was required to sign, I espied the words ‘signature of recruit’. I agreed to sign if I might cross out the words ‘of recruit’, but he emphatically declared, “No you mustn’t cross out anything.” Whereupon with calculated deliberation, I handed back the pen and firmly declared, “No, I’m not signing it.” He shrugged his shoulders with the remark, “Just as you like, it makes no difference to me,” and I was forthwith dismissed.

My escort then took me to meet the Company Officer, who upon hearing of my dissentient exploits directed that I be removed to the guardroom. On the way I indignantly enquired of my escort, “Why the guardroom?” to which he replied, “Because you ain’t safe to be allowed outside.” Arriving at that place, I was handed over to the sergeant of the guard, who locked me into the common room, which I entered with a smile. Here, perceiving a group of three men at the opposite end who like myself were in civilian clothing, I made towards them. I was saluted with the question, “Are you a CO?” and answered, “Yes!” “Ah! I thought you were when you came in with a smile like that,” then with a laugh, “The soldiers who come in here, come in with a scowl and a curse.”

Then followed mutual introductions, the small company of men being Runham-Brown, Adams and Simons. The first is one of the most delightful characters that it has ever been my good fortune to encounter. His tranquillity of mind and calm serenity under all provocation and his tolerance of all opposing opinion are truly wonderful and an inspiration to behold, for one of such a fiery disposition as by nature, I am myself. Indeed some such character as he, must surely have inspired the lines: -

An inner light, an inner calm,

Have they who trust His mighty arm.

J. J. Lynch.

Of Adams I saw but little, for we lost him at the parting of the ways, owing to domestic circumstances which caused him great anxiety. But the character of Simons was the source of endless amusement for us. He was one of those peculiar characters who are never happy except in opposition and his very agnosticism seemed to savour more of his love of contradiction than of deep conviction. But he was a very likable little man and when excited in argument, his voice rose to a curious squeak, which was the cause of much stifled laughter among us. However this outstanding trait of his character could be extremely irritating, for it definitely precluded the possibility of finding common ground, when serious matters were under discussion.

With my introduction to these three comrades, the episode of my arrest came to its termination and I entered upon that phase of the adventure that brought me within the confines of the army.

Whose Image and Superscription?

The story of a First World War conscientious objector