CHAPTER 32

DISCHARGE

Hitherto hath the Lord helped us.

1 Samuel VII, 12.

My discharge from the army is a striking example of the astounding, but exquisite humour of red tape. On Thursday April 24th, 1919, I received the expected telegram from the Adjutant at Mill Hill Barracks, instructing me to return there the following morning. I therefore caught the 6.30 a.m. train for London on Friday morning and sought out an empty compartment in the hope of being able to travel alone. But just before the train left, a lady burst in and seated herself opposite me. I immediately recognised her as being a Sunday School teacher from the Wesleyan Chapel, which had been my spiritual home of my early years and at one time had included my younger sister and my wife in her class. However, she on her part did not recognise me at once, being in a somewhat flustered state by her belated arrival at the station. The train had not proceeded far, when with a measure of surprise she recognised me and we entered into conversation. At first our remarks were confined to generalities such as the weather etc., but at length we got into more particularized channels. Eventually she asked, “By the way, what’s become of your sister? I never see her at chapel now.” “No, I don’t suppose you ever will again, she’s joined the Christadelphians.” “The Christadelphians, they’ve got some peculiar views, they have.” Now I was at this time, feeling decidedly hostile towards the Christadelphians myself, but this observation rather nettled me, as it seemed to cast aspirations on my sister’s thought processes. Under the circumstances I thought a little leg pulling was in order, so with a mischievous twinkle in my eye I retorted, “Well you would expect peculiar ideas to be associated with a peculiar people wouldn’t you? The apostle tells us that the followers of Jesus are called to be a peculiar people.” The look of astonished consternation on the face of my companion would have been an inspiration to an artist on the staff of Punch. My fellow traveller relapsed into silence and did not speak further, until the time came for us to part company.

Presently we reached Radlett where I left the train, bidding my fellow traveller a polite, “Good morning” which she pleasantly returned. Then I set out on one of the most of delightful country walks. The morning sun was warm and bright, shining from a cloudless sky. Birds warbled, flowers nodded their brightly coloured heads and the five miles was over all too soon, as I found myself within the precincts of the barracks, with all the irritating sights and sounds of military activity.

At 10 o’clock, we were all with the exception of Stephen Thorne, gathered in the corridor outside the orderly room. The minutes dragged slowly by while we experienced apprehension, feeling that our own integrity was at stake, due to our comrade’s delinquency. Fred Ballard voiced our doubts by observing, “I’m very sorry about this, as it’s bound to give a bad impression.” At ten minutes past the hour, to the very great relief of the rest of us, Thorne came running in, very much out of breath and explained that due to a traffic jam, he had missed his intended train. As the Adjutant was still awaiting the arrival of the Colonel, no harm was done.

Now followed a farcical comedy that even Gilbert and Sullivan would find it hard to exceed on the stage. To surmount the difficulty that no more COs were to be court-martialled, after the Adjutant had read out the charge, the Colonel himself sentenced us to ten days detention. This ridiculous attempt to preserve the dignity of red tape was in itself a contravention of a Government regulation that COs were to serve their sentences in a civil prison. Moreover we had all been remanded for a court-martial and therefore, according to regulation, could not be disposed of until we had appeared before the court.

When we left the orderly room, a fully armed guard was waiting to take us to the detention barracks at Wandsworth Prison. So once more we took the old circuitous route with its numerous changes of trains to the other side of London. Arriving at our destination we were taken to the offices of the detention barracks and immediately formally discharged from the army. We were given railway passes to take us to our home stations. This arrangement was made for the other four, these being close to the barracks from which we had just been brought. The clerk at first demurred at my request for a pass to Luton, but I insisted, pointing out that it was the place where I had been arrested and from where I had been brought by a Mill Hill escort. Further it was from where I had come that morning. In the face of these arguments, he forthwith made out the desired document.

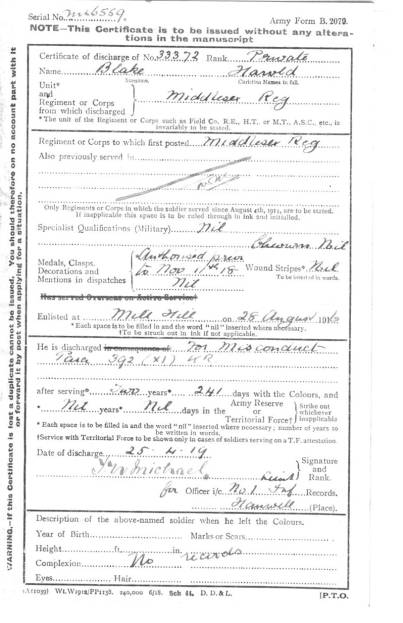

Some weeks later my discharge certificate arrived by post and I now prize it as one of my most valued possessions. I regard it with as much pride as does the soldier with his war medals, as a badge of honour won in the service of the King of kings. With especial pride do I view the words ‘No records’, under the description of the soldier. They are the outward sign and the evidence of victory in the long struggle with those modern representatives of Caesar, that Caesar had failed to impress upon me his image and superscription.

The certificate itself is not without its excessively funny side, as any one will find if he is in a position to refer to the King’s Regulations. If he would turn to the section mentioned under which the discharge is made (Para 392 x1), he will there be solemnly informed that the subject of such a discharge, will be liable to a sentence of imprisonment, should he ever attempt to enlist in the army again. I very much doubt if that clause was ever brought into operation concerning a CO who had changed the colour of his coat and felt like he would now like to a soldier of the King of England.

Whose Image and Superscription?

The story of a First World War conscientious objector