CHAPTER 24

THE

QUAKER MEETINGS

This also that she hath done shall be spoken of for a memorial of her.

Mark XIV, 9.

In this chapter, it is a pleasing duty to pay a warm and glowing tribute of appreciation to the Society of Friends. They rendered invaluable support and encouragement to us COs and if it had not been for their interest, the task of witnessing complete loyalty to Jesus, against the embittered spleen of the most powerful empire the world has ever seen, would have been infinitely harder.

Of all the bodies calling themselves Christian and professing to be followers of Christ, the Quakers, and THEY ONLY, offered the cup of cool refreshing draught in the name of Jesus to those in the fiery furnace of persecution and verily, they shall not lose their reward.

I did not attend the Quaker meetings until my third sentence and long before this time, the Friends had fought and won the right of all and sundry to address the gathering. When the first Quaker meetings were held at Wormwood Scrubs, the prison officials had disallowed the practice of prisoners addressing the congregation. The Society of Friends had carried the matter to the Prison Commissioners, pointing out to them that this procedure was their normal practice and that the government regulations allowed for prisoners to attend a meeting under the supervision of their chosen sect in accordance with their usual practice. The Prison Commissioners had no alternative but to back down and instructed the officials not to interfere.

Quite a number of the Quaker meetings remain fresh in my memory. The one that created the deepest impression on me was held on September 19th, 1917. One of the visiting chaplains (they usually came in pairs) was Dr. Henry Hodgkins, a medical man who had been engaged in both physical and spiritual healing in China. He was at this time the president of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, an organisation against military service, who adopted as their basis 2 Corinthians V, 18-20, ‘… Christ has given to us the ministry of reconciliation …’.

Dr. Hodgkins spoke that day on Hebrews VI, 18-20. He explained firstly that the original Greek could not be adequately rendered into English, because it contains words for which there is no English equivalent. He painted the picture of the rocky coast of Greece with a violent storm raging. Through a narrow gap is the entrance to a harbour, where the water is calm and still. Outside is a Phoenician trading vessel in danger of being dashed to pieces to the rocks. The mariners despatch a small boat carrying an anchor attached to the ship and drop the anchor in the peaceful waters of the harbour. The speaker then mentioned that the Greek word translated as ‘forerunner’ is the name of that small anchor carrying boat. So the idea being conveyed, is that Jesus is like the small boat, overcoming the dangerous storm to secure a firm anchor for us.

We listened spell bound with absorbed interest, while Dr. Hodgkins unfolded his exposition of this passage, painting a fascinating picture before our eyes, with his marvellously graphic descriptions. I for one will hold the memory of that beautiful address for all time.

My memory has also retained a clear impression of another meeting, in which Runham-Brown addressed us. He spoke of a footpath running parallel with the high road through Epping Forest. When the main road is crowded with vehicles and pedestrians all hurrying onward, how much more restful, refreshing and enjoyable it would be to retire to the quiet shady footpath. In like manner we should make the period of our lives through which we were now passing, like that that tranquil work along the foot path and thus use our seclusion to its best advantage.

Another meeting that made a lasting impression took place shortly after Concessions, 243.A. was introduced. On this occasion, Tom Drayton gave us some sound admonition on the right use of the power of speech, now that we were allowed the privilege of conversing once again. He remarked that, as was his usual custom, he would conclude with his text, Proverbs XXV, 11, ‘A word fitly spoken is like apples of gold in pictures of silver’.

One other Quaker address I have retained in my memory was by Stephen Thorne and he took John XII, 36, ‘While ye have light, believe in the light, that ye may be the children of light’.

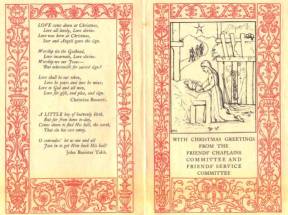

Robert Penney, one of the Quaker chaplains always arrived with a huge buttonhole of flowers and Alfred Kemp Brown, another chaplain, often brought an arrangement of leaves. Such things are trivial in themselves, but gladdened our eyes and cheered the hearts of those who loved nature. And as one of the chaplains said, “No warder would dare to interfere with the Chaplain’s buttonhole.” But perhaps of them all, the chaplain whom we were most delighted to see, was Frederick Saintie, who with his unfailing cheery smile and encouraging words, always cast beams of sunshine along the dreary path that we had to tread.

The prison regulations permitted the nonconformist chaplains to visit once a fortnight. On alternate visits i.e. once in four weeks, the Quaker prisoners were all gathered together in one large meeting. I remember that at one of these gatherings, a certain officer was told to be in attendance as a watchdog. This man belonged to the Salvation Army and bore the nickname both among officers and prisoners of Jerky Jack, due to his decidedly eccentric behaviour. During the meeting, someone asked for the hymn, which has the refrain, ‘Sing it o’er and o’er again, Christ receiveth sinful men’. Jerky Jack thoroughly enjoyed himself during the singing of that hymn and I was amused at the extravagant and abandoned enthusiasm he devoted to it.

On the alternating visitations of the chaplains, it was intended that they should interview each man individually, but there were far too many Quakers to render this a practical proposition. Therefore we were admitted to the Friend in parties of sixes and had some very interesting conversations between him and ourselves. On such occasions, Mr. Saintie always commenced with a few words of prayer, all kneeling side by side on the floor. I found these quietly spoken words of thanks and request for courage a source of astonishing strength in the determination to continue to the end, if the need should be so.

Whose Image and Superscription?

The story of a First World War conscientious objector