CHAPTER 2

THE

LOCAL TRIBUNAL

It shall be given you in that same hour what ye shall speak.

Matthew X, 19.

Immediately after the Second Military Service Act became operative, I began to bestir myself to secure a tribunal hearing. The first question I had to decide was whether or not I should appeal to the tribunal at all, for I could not disguise from myself the fact that an earthly tribunal can never be a fit and adequate judge of such a thing as conscience. Nevertheless since the legislators had presumably endeavoured to meet such cases as mine by the inclusion of a conscience clause, was it not my duty to allow that Act an opportunity of vindicating itself? Possibly I was influenced towards the negative view by a shrinking from the publicity, which the ordeal of appearing before the tribunal would entail upon me. A shrinking which was natural to my reserved and reticent disposition.

Next I had to decide which tribunal? I was engaged in business at Northwood, but the only place I could consider as home at that time was Luton. Moreover and most important of all, both my father and mother had been known to several members of the Luton Local Tribunal for many years, whereas not one of the Northwood Tribunal was even acquainted with me. To ask the latter to judge of such a thing as conscientious objection was therefore likely to be grossly unfair to the members of that tribunal themselves. Having reasoned the matter thus, I decided in favour of the Luton Tribunal.

That question disposed of, I wrote to my wife requesting that she secure an application form and forward it to me. Meanwhile I set about procuring evidence to support my claim. With this purpose in view, I recalled an incident from ten or eleven years previously, concerning a debate held under the auspices of the Luton Waller St Wesley Guild on the question ‘Is war a necessity?’ The leader of the negative side was an old friend of the family and curiously enough the only support and votes, which he obtained, were all from members of my family. This singular circumstance enabled him to recollect the incident when I applied to him for a letter regarding myself to the tribunal. Thus was established the fact of long standing conviction and this letter enabled me to confound the tribunal on one question.

Next I applied to a former employer to confer upon me written evidence of my all-round conscientiousness. Although he disapproved of and endeavoured to turn me from the purpose for which I wished to use this, when he perceived that I was resolute, he readily complied. This employer had been my Society Class Leader at the Wesleyan chapel and to my unbounded astonishment he quoted ‘He that hath no sword, let him sell his garment, and buy one’ (Luke XXII, 36). I did not attempt to argue with him, but contented myself by intimating that I considered he had misjudged Christ’s central issue when he spoke those words. He concluded by saying in a half-bantering, half-reproachful manner, “You are an obstinate young man”.

I now learned from my wife that the required application form was not yet ready, but that she would send me one as soon as obtainable. In due course it reached me on June 4th and I returned this with the required particulars duly filled in. I received a postcard from the headquarters of the Bedfordshire Regiment, which were at Bedford, asking if I were willing in anticipation of ‘calling up’ to undergo a medical examination in order to save time in classification. I returned the card immediately with NO! written in a large hand on it. On June 7th I received my second yellow paper this time from the Bedfordshire Regiment and I returned it by hand to the Luton office with the word ‘appealing’ written across it.

The dread of appearing in public was ever upon me and I thought often with a sinking heart how unworthy an exponent I was of the high ordeal of a Christian life. I heard in my own mind the sarcastic tones of some scoffing opponent, “What a saint this fellow pretends to be, but is he any better than another fellow who joins up?” At such times I drew courage and a measure of confidence from Martin Luther’s beautiful paraphrase of Psalm 130, which commences with the lines: -

Out of the depths I cry to thee,

Lord God! O hear my prayer!

Incline a gracious ear to me,

And bid me not despair.

Many a time while cycling from Northwood to Luton have I sung this hymn over as I sped along the road. As the sublime truth and promise contained in its words have borne upon my mind, my spirit has grown calm and confident again. I have always felt at one with nature and in close communion with nature’s Lord when alone in the open. It is for this reason that at most times, I prefer solitude in my country rambles and the presence of a second person seems to me to introduce a note of artificiality, which jars and disturbs the harmony of my contemplative thoughts. But amid the solitude of field and wood, I have been able to enjoy the uninterrupted flow of my own thoughts as I have contemplated the illimitable mystery of nature, with its marvellously planned and awe inspiring cycles, comprising wheels within wheels. I have thus realised what it is to stand on holy ground and in some measure understood in what manner strength came to Christ from his lonely vigils among the hills of Galilee.

Where Jesus knelt to share with thee

The silence of eternity,

Interpreted by love.

J. G. Whittier.

On June 21st, just as I was about to enter upon my day’s duties, I received a letter from my wife enclosing a communication from the clerk of the Luton Local Tribunal stating that my case was to be heard on June 21st, i.e. that same day. The notice had been received the previous day, but of course a day had been lost in forwarding it on to me. With the notice of hearing was a paper containing the ten questions. I just had time to read through these questions rapidly before entering the shop and perceived immediately how well they had been planned and how tripping they were for any man not sure of his ground. I calculated that the first nine would give me no trouble, but the tenth was a nasty one. I had to banish them from my mind, lest owing to divided attention, I should make some serious error in my work. The clock reaching the hour of one brought my duties to a finish that day until 10 p.m. I retired for my mid-day meal, then after a hurried change, I mounted my bicycle and rode to Luton, arriving there about 4 o’clock. After washing and changing I applied myself to answering the ten questions. I first made out my answers in the form of rough notes, intending subsequently to copy them into more legible form. But when I had finished my tea, I found that my time had expired and that I must set out for the town hall if I were to appear on time for the hearing of my case. Accordingly I departed with my roughly prepared answers and entering the building, seated myself in the anteroom where I encountered an old school friend, who was also there to appeal on conscientious grounds.

9 Cromwell Road, Luton

Photo: H Blake

I append here the questions with my answers:-

1. State precisely on what grounds you base your objections to combatant service.

2. If you object also to non-combatant service state precisely your reasons.

Answer: These present to me the same question and I therefore answer them as one. My objection is not so much an objection to military service as an objection to war. The participation in which I believe to be wrong and unchristian, according as I interpret the teachings of Christ, as contained in the New Testament.

3. Do you object to participating in the use of arms in any dispute, whatever the circumstances and however just in your opinion, the cause?

Answer: Yes.

4. Would you be willing to join some branch of military service engaged, not in the destruction but in the saving of life? If not, state precisely your reasons.

Answer: No. As stated above, I object to participation in war in any capacity. All military service is convened for the prosecution of war, and all is part of the military machine, which exists for that purpose only.

5a. How long have you held the conscientious objections expressed above?

Answer: These principles have been engrafted into my character with my earliest training, received from godly parents.

5b. What evidence can you produce to support your statement? Please forward written evidence (from persons of standing if possible) which should be quite definite as to the nature and sincerity of your conscientious objections.

Answer: Vide letter from Mr. J. H. Webb.

6a. Are you a member of a religious body and if so what body?

Answer: I am not now a member of any religious body, but for years I was a member of the Wesleyan Church. The duties connected with my calling, now render it impossible for me to fulfil the conditions of membership, nevertheless I continue to attend the services of that church and I still regard myself as Wesleyan.

6b. Is it one of the tenets of this body that no member must engage in any military service whatsoever?

Answer: No

6c. Does the body penalize in any way a member who does engage in military service, if so in what way?

Answer: No

6d. When did you become a member of that body?

Answer: As a child.

7. Are you a member of any other body etc?

Answer: None.

8. Can you state any sacrifice which you have made at any time because of the conscientious objections now put forward?

Answer: I was compelled to leave my last situation, which in fact has involved me in heavy expense. My home is broken up and my wife obliged to return to her previous occupation. I think you will realise that the last is a very humiliating circumstance for any man.

9a. Assuming that your conscientious objections were established, would you be willing to undertake some form of national service (other than your present work) at this time of national need?

Answer: Not as a condition of exemption from military service.

9b. What particular kinds of national service would you be willing to undertake.

Answer: I consider that the care of the health of the nation is work of the utmost national importance. As I have spent years in training and study to fit myself for this work, I cannot conceive of any undertaking where I should be of more service than in that for which I am specially trained.

9c. Have you since the war broke out, been engaged in any form of philanthropic or other work for the good of the community?

Answer: None other than dispensing (under my employer) for a V.A.D. hospital.

9d. What sacrifice are you prepared to make to show your willingness (without violating your conscience) to help your country at the present time?

Answer: I am prepared to make every sacrifice to help my country to preserve its TRUE liberty.

10a. If you are not willing to undertake any kind of work of national importance as a condition of being exempted from military service, state precisely your reasons?

Answer: To accept any condition of exemption from military service would be to me a tacit acquiescence in the prosecution of war.

10b. How do you reconcile your enjoying the privileges of British citizenship with this refusal?

Answer: Before I can answer, I must first know what is meant by the privileges of British citizenship. If is meant:-

1. The vote this I have never had.

2. The law - This I have never had the occasion to use, but justice has to be bought and the question of privilege does not therefore enter.

3. Freedom of speech - Does not now exist.

I deny that these are privileges, but should be the right of all men whether British or otherwise.

The reader will realise that I based my position solely on the one central and all-important fact: that the commands of Jesus definitely and conclusively preclude the ideas of his followers engaging in war. Like all great issues concerning the gospel, if one goes to the fundamental principle it becomes astonishingly simple. When I coupled questions 1 & 2 together, I did not realise the significance at the time, but I had seen beyond the petty question of military service to the larger issue of WAR service. This is an illustration of Christ’s promise which heads this chapter. I followed the light that had been given me and by it I readily discerned the sinister and insidious character of all the various schemes that the government brought forward in their efforts to solve the puzzling and irritating question of the absolutionist conscientious objector. I insisted on absolute exemption to the end.

My answer to question ten was that which at first occurred to me and with time for further consideration, it should probably have been very different. But I have no regrets. Upon thinking it over afterwards, I was convinced it had been put forward in a spirit of sarcastic spleen and an attempt to make the way of faithfulness to Christ appear ridiculous. I answered sarcasm with sarcasm, or in other words, I carried into effect the wise mans counsel to answer a fool according to his folly, lest he be wise in his own conceit.

When I had waited some minutes in the anteroom of the Town Hall, an attendant called my name. Having indicated my presence, she asked for the questions and answers and departed with them to the room where the tribunal was in conclave. I use this last word advisedly, the secrecy reserved over the proceedings would call forth my strongest denunciation. Some ten minutes later I was directed to present myself before the assembled members and greeted with a request from the clerk for my name and address. I replied with the address on my registration card, namely 9 Cromwell Road, Luton. Then followed, “You are in business in Northwood?” Yes. “You live there?” I had entered the room feeling nervous, but sensing a battle, became alert and at ease. Perceiving the drift of the questioning I replied, “I have a temporary room there.”

Then occurred several minutes passage of arms between us, he trying to get some sort of admission from me that Northwood was my place of residence, while I persistently avoided being trapped. Failing to get a reply that gave him the advantage he desired, he at length snapped out in irritation, “The case will be sent to Northwood.” I tried to protest with conclusive reasons why the Luton Tribunal should here my case, but realising that the matter had been decided before I had entered, I rose to leave.

As I was departing, I noticed one of the members sitting apart at the end of the long table having apparently dissociated himself from the proceedings. He was an old friend and as he caught my eye he nodded and smiled in a manner, which suggested encouragement. This lightened my heart and I entered the front gate with a smiling face, which unfortunately filled my mother with the idea that I had been granted exemption. I myself knew that my only chance had failed and when she asked what had transpired I replied, “Nothing, they have flunked a decision. There is no help for it now, I shall have to go through the mill.” She was optimistic, but I pointed out that better men than me had been unable to secure exemption. In spite of this she persisted in her faith and my heart sank as I realised the crushing weight of sorrow that was in store for her.

The next development in the drama was a notice of hearing for July 3rd from the Northwood Local Tribunal. When my name was called on the evening of that day, I was directed to seat myself in the chair facing the tribunal members. The whole proceedings seemed to be a one man show, the individual in question being the clerk. The case opened with his reading of my answers, still a conglomeration of alterations, deletions and superimposed additions, which was the state in which I had had to relinquish the paper. There then followed a few questions relative to my answer to question 6a, the clerk asking about my membership of the Wesleyan Church and the circumstances which rendered my compliance therewith impossible. I explained that membership depended upon attendance of a Society Class meeting, pointing out that, owing to my work in the evenings dispensing urgent medical supplies, I was unable to attend such meetings. The clerk next turned to question 9c remarking, “I see you are dispensing for a V.A.D. hospital. What is the difference between that and dispensing in the R.A.M.C.?” This question although quite a natural and logical one, caught me unprepared and I replied that I considered there was a great difference but could not state exactly what it was on the spur of the moment. Then ensued a period of questioning with regard to my employer’s business. I considered this was getting away from the subject under consideration, besides displaying an unwarrantable inquisitiveness towards my employer’s affairs and in consequence I pointed out that my appeal was in no way connected with business. Thereupon the voice of my employer was heard calling out that he was present and willing to answer any questions, but the clerk declined this challenge. Turning to the Military Representative, he asked him what he had to say. His reply as far as I can remember was, “I object to this appeal. I see the man has a knowledge of dispensing and would be very useful to us in the R.A.M.C.”

My case was then put aside in order to hear the remainder for the evening. The room was then cleared for the tribunal to deliberate in private. My settled opinion that the appeal would not meet with success was further confirmed by the Military Representative being allowed to remain. It seemed the prosecuting council were allowed a vote in the verdict, while the defence was excluded. All cases being decided, the doors of the chamber were again thrown open and the clerk announced the various results. My own case being reached, the clerk addressed himself to me saying, “Well Mr. Blake, we are quite convinced that you have a genuine conscientious objection,” here I inclined my head and quietly remarked, “thank you.” The clerk proceeded, “but we think you ought to do something and therefore give you exemption from combatant service on the understanding that you become a dispenser in the R.A.M.C.”

This decision was in itself both illogical and absurd. I had shown that to me, questions 1 and 2 presented the same question. Therefore if I had proved conscientious objection to one, then I had at the same time proved objection to the other and therefore in practice there was no exemption at all. Yet it was a handsome bait, which however I was not temped to swallow. It meant immediate rank of sergeant with pay and separation allowance for my wife, on a comparatively liberal scale. I would not be exposed to the dangers of the front line, but be at a station overseeing the dispensing by the rank and file. All this flashed through my mind, but I stayed to hear no more. Rising from my chair I exclaimed indignantly, “I can’t accept it,” and left the building in disgust.

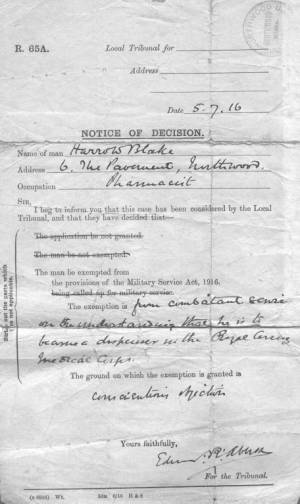

On July 6th I received by post the formal Notice of Decision, my reply to which was the obtaining of an application form for appeal.

Whose Image and Superscription?

The story of a First World War conscientious objector