CHAPTER 15

ASSOCIATED

LABOUR

With good will doing service, as to the Lord, and not to men.

Ephesians VI, 7.

On account of a Government concession to COs, the first month of solitary confinement was waived and we went straight away into associated labour. The COs were disposed to one corner of the workshop, on the extreme right of the watching officer and were at first occupied with the continuance of their cell tasks, i.e. sewing mailbags. By what must have been an oversight, they were positioned with their backs to the officer, who sat on the observation bridge, so that for a few days they were in the enviable position of being able to converse quietly without discovery. But as is often the case in these situations, they unconsciously became more and more animated in their conversation, particularly as they entered deep subjects, until two of them were detected. One of these was an agnostic (our old friend Mr. Simons), while the other was a Christian of a rather sentimental evangelical bent and the latter was ardently trying to convince the former of Christian truth. Consequently we were all ordered to turn round and so lost our short-lived advantage.

Before this happened however, I was one day sitting besides Philip Millwood (we sat on stools which we carried from our cells). As we worked, we engaged on an interesting discussion on the physiognomy of the ordinary prisoners who were working on tables in front of us and agreed that most had faces that reflected quite good character traits. We thus concluded that the worst criminals never get condemned to prison.

Before long, most of us were relieved of the monotony of sewing all day. By twos and threes we were placed on other tasks. First some were put onto sewing machines, then Runham-Brown and Millwood were detailed off to the cutting table, where the mailbag canvas was cut up into the required shapes and sizes. Afterwards the Taskmaster adopted a party of three as his porters. This duty consisted of accompanying the officer to the cells to deliver supplies of raw materials and to collect the finished work. In passing I might mention that a prisoner who was subject to the punishment diet with close confinement, had the choice of continuing his cell task during that time or not. When any of our number fell upon this misfortune, we utilised these porters to supply extra food to these prisoners, concealed in the canvas and other materials.

Horace Jones and myself were the next to be transferred and to the packing table. Jones’s task was to straighten out the mailbags and fold them in the prescribed manner. In this form they were ready for me to stencil with the type number, the GPO letters and the broad arrow. Jones then tied them up in dozens, ready to be taken to the stores. Taking into account the type of worker and the working conditions, it is not surprising that a considerable number of bags exhibited faulty workmanship. A common defect was the inclusion of a pleat in a seam, where the sewer had failed to get the two edges of the material to register along the entire length and had thus overcome the difficulty in this simple but improper manner. Thereafter the cell tasks of the two of us working on the packing table consisted of the rectification of faults, officially designated repairs.

My second sentence was still quite young when Philip Millwood began to astonish and thrill us in the workshop by his nonchalant behaviour. On one occasion he and Runham-Brown had cut up sufficient canvas to last us some days and so were occupied in sewing, as they leaned against their table. The two were physically very similar with very much the same tall and thin build. As they faced the observation officer it was perfectly evident that they were quietly conversing together, although some two yards apart. The officer glanced doubtfully in their direction once or twice, not sure if his senses were deceiving him, it being unthinkable that two prisoners should so fragrantly defy the rules. Eventually he resolved the point to his complete satisfaction so he called out, “Forty-eight, stop talking!” Neither Millwood nor Runham-Brown took the slightest notice but continued their work and conservation. The officer repeated his command and then in annoyance, “Forty-eight, are you deaf?” Millwood looked up innocently and meekly asked, “Do you mean me?” “Yes, of course I do, stop talking.” Millwood with well feigned blank astonishment said, “Oh, then I’m not forty-eight and I’m not deaf.” He then went on with his work as though nothing out of the way had happened. By this time the COs were bending over their work, nearly exploding with suppressed laughter and the other prisoners were gazing with open-mouthed astonishment at this daring disdainer of authority. The officer evidently realised that he had made himself look foolish and so wisely refrained from blustering threats, but came down off the bridge and said to Millwood quite quietly, “What is your number then?” Taking hold of Millwood’s jacket to see the cell badge and continued, “Oh I see, forty-seven, all right I’ll remember it next time.” He then went back to his station and to our great amazement, nothing more was heard of the affair.

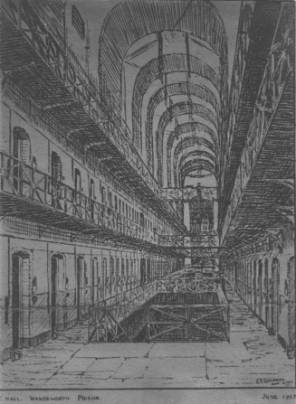

Hall C, Wandsworth Prison

From the sketch by

G E Gascoyne

One morning Jones and I were working at our table, when Joe Goss, one of the porters, was filling in time by sewing at an adjacent table. He engaged our attention by clandestinely telling us of a Labour Party member with pronounced republican views, who had in a moment of sentimental patriotic fervour, taken a commission in the Territorial Army. How he managed with the oath we did not hear. At a social function of the regiment he had refused to stand during the National Anthem and in consequence was court-martialled and cashiered. Jones with astonishment at such inconsistency remarked, “What a funny position to find himself in. He was caught between the devil and the deep blue sea.” With a sense of mischief I asked, “Which do you suggest is the devil, the King or the Labour Party?” The result was that all three of us were suddenly under the necessity of disappearing under the table in search of some fictitious article, lest the officer should see our convulsive laughter.

For stencilling the bags, I was supplied with a paintbrush of a size known to painters as a sash brush. However the bristles were too long, so I bound them with string so as to leave the end sufficiently stiff for the job. When we returned to the cells, the Taskmaster locked this brush and the black paint away. In spite of this, several brushes disappeared from the cupboard, so the officer told me to take the brush back to my cell, in the bag with my other tools. Now on a board outside each cell is a card detailing the tools supplied to each prisoner and in this instance, the Taskmaster forgot to add the brush to my list.

After a time the brush got clogged, so one evening I unbound the bristles and washed the brush in my cell washbowl. I dried it as much as possible by twirling it between my palms and finally put it on my upper shelf with the bristles overhanging, to complete the process. In the morning after returning from exercise, I was surprised to find that I was down for report, this being indicated by a card bearing a large letter R stuck in my notice board. I was detained in my cell after the others had departed to the workshop and at about 10 o’clock was conducted to the Governor’s office and lined up in the queue outside. When my turn came, I discovered that I was accused of having a contraband article in my cell, to wit the above-mentioned brush. My accuser was an officer, who was an old soldier who had been through the South African war and hence was very hostile to COs. Apparently he had been prowling around our cells during exercise time, in the malevolent hope of finding some trouble and imagined he had found what he was looking for in my case. The Governor asked me to explain, where upon doing so, an officer was despatched to fetch Mr. Hayter the Taskmaster. When he corroborated my statement, I was returned to my cell vindicated of the charge. But as I was leaving the office, I heard the Governor reprimand my accuser for going out of his way to interfere with prisoners, who were in charge of other officers.

Consequently I became the object of the especial malice of this particular officer. Indeed his subsequent conduct seemed to suggest that he held me responsible for his reprimand and from that time forward he then commenced a campaign of persecution against me. Most of his efforts came to nothing, for I made it a point of policy to appear utterly unaware of his disconcerting tactics, such that his actions fell flat and he only succeeded in procuring exasperation for himself.

Whose Image and Superscription?

The story of a First World War conscientious objector