CHAPTER 12

PRISON

SECOND SENTENCE

He that delivered me unto thee hath the greater sin.

John XIX, 11.

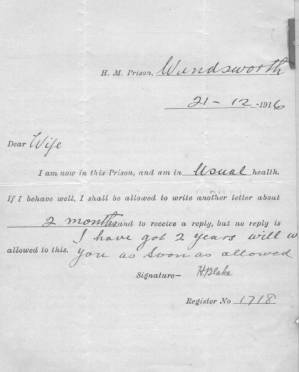

On December 21st 1916 following the promulgation of sentence, Simons, Brownutt and myself were released from our cells to take an early dinner together in the corridor outside. This was brought to us in basins and as no cutlery was provided, we had to eat with our fingers. Simons was a vegetarian, and how he managed to keep alive both at the barracks and in prison was a matter of wonder to me. No provision was made for food faddists, vegetarians being unknown amongst ordinary lawbreakers. Eventually, at a time when I was well into my third sentence, the Prison Commissioners yielded to constant importunity from vegetarian COs and instituted such a diet. Long sentence prisoners were weighed at regular intervals and very probably, a serious weight loss from such prisoners induced them to act in the matter.

Having consumed all the solids of my dinner, I lifted the basin to my lips in order to drink the gravy. Simons raised his hands in horror and his voice rose to the curious high pitched squeak which I have mentioned in an earlier chapter and in his excitement he exclaimed, “Oh, look at him poisoning himself.” Both Brownutt and I were reduced to a state of helpless laughter.

After dinner we were ordered outside to take our places besides the armed guard, which was to escort us to the prison, and almost immediately our two new comrades joined us from the common room. We were taken by the same route as before to Wormwood Scrubs, but had not proceeded far from the barracks gates before Miss Martha Fox, daughter of Dr. Fox of Hampstead Garden Suburb and a prominent member of the Society of Friends, joined us. This incident showed us that although the army officers had not permitted any communication with us, yet a close watch was kept to see when and where the military moved us and there is not the shadow of doubt that many dark and secret deeds were thus circumvented. On one occasion when the military moved a party of COs across the channel to the war zone in France, secretly they thought, they were immediately detected by the watchful Quakers. Their action, which was in contravention of Government instructions, was reported to the Prime Minister (Mr Asquith), who forthwith ordered their recall, so that the treacherous and dastardly designs were frustrated.

At Wormwood Scrubs we were marched as before into the entrance gateway between the inner and outer gates, where we waited while the sergeant’s papers were scrutinised. Having scanned the papers, the prison officials refused to take the three second sentence men, pointing out that only first sentence COs could be taken by Wormwood Scrubs and this because they were to go before the Central Tribunal which sat there. The two new men therefore were accepted and rest of us turned around. Outside we saw Miss Fox still waiting, in order to verify that the escort returned without the prisoners, so as to confirm their location.

The sergeant of the escort guard was now in

a terrific quandary. His prisoners’ railway passes only took them to Wormwood

Scrubs and only the escorts had return passes to Mill Hill. After some cogitation he decided on taking

what must have appeared to him, a tremendous risk. He ordered the escort to return to the barracks, while he himself

took us on to Wandsworth, paying the expenses for the three of us plus himself

out of his own pocket. By what route we

went I do not know, but I remember we traversed much the greater part of it by

tramcar. Throughout we enjoyed

unrestrained freedom of conversation with Miss Fox and bade goodbye to her at

the prison gates. After the sergeant

had handed us over to the prison officers and concluded his business with them,

he astonished us by wishing us a most cordial and friendly goodbye, which

naturally seemed quite out of keeping with his commission.

Our reception into

Wandsworth Prison was very different to that experienced at Wormwood

Scrubs. We were dealt with in

alphabetical order and hence my turn came first. While the other two sat on a bench in the corridor, I was called

into the reception office, where the officer on duty asked me a number of

questions relating to my personnel details and noted down the particulars. When I replied in the affirmative to his

question as to whether I was married or not, he said, “What does your wife

think of you now? Does she stand with you

in this?” Perhaps the reader will

understand something of my feelings of pride in my wife, when I say that I

replied with a radiant and happy smile, and an emphatic, “Yes!”

Amy Blake

d.1952

Photo: W J

Roberts, Luton

The interview over, he recorded my physical description, repeating the details aloud as he wrote and then requested me to strip. I have designated it as a request rather than an order, because he was such a kindly soul and although an uneducated man, he had that hallmark and ‘sine qua non’ of the true gentleman. This consisting of a thoughtful consideration for the feelings of another and speaking with a gentle demeanour. When I had divested myself of my clothes and stood before him naked, he examined my body for any marks, or scars, which would serve for identification purposes. In this I further augmented my golden opinion of him when he explained why he was going through this routine, an explanation that of course he was under no obligation to give. His friendly remarks seemed to take away all occasion for resentment, and render the circumstances natural and seemly.

Behind the officer’s

desk, the wall of the room was broken up into a series of alcoves containing

baths, each recess being of just sufficient width to accommodate one. By this arrangement, access to the next room

was gained via the baths. The officer

having completed his records, directed me to take a bath and emerge on the

other side. Here I found the prison

clothes awaiting me and was struck with wonder at the remarkable array of

colours which the habiliments presented to me.

The prison uniform for a soldier undergoing hard labour is dark grey,

almost black and that was the sort of thing in which we had been dressed in at

Wormwood Scrubs. This uniform consisted

of salmon-pink trousers, a chocolate-brown jacket and waistcoat and a blue

Glengarry cap. I afterwards learnt that

this is the uniform for a second division prisoner and I believe the

explanation of why it was supplied to me, lies in the fact that the officials

at Wandsworth Prison had in the COs a class of prisoner which was new to them

and they were rather uncertain how to respond.

When I had dressed, I

returned to the corridor and took my seat on the above mentioned bench to await

the other two. After we were all ready

and had waited a little time, the Assistant Chaplain came to interview us. As it was already past the time when the

prisoners are locked into their cells for the night and only the night officers

were on duty, we were taken to temporary cells for that night, these being in

Hall B, Ward 2. I was placed in Cell

12.

The ground plan of the

ward halls at Wandsworth was entirely different to that at Wormwood

Scrubs. At the latter place, the halls

were built as separate detached structures, parallel to each other with

exercise yards and workshops occupying the spaces between them. At the former, they were arranged like the

spokes of a wheel. The hub at the

centre being occupied by the control desk and various offices, such as the

Governor’s office, the Chaplain’s office etc.

The spaces in the recesses between the spokes were utilised as exercise

rings, circulating kitchen gardens and one or two of the smaller workshops,

such as the carpenters’ shop. There

were four halls of cells and the main entrance to the edifice, which faced

towards the main outer gate of the prison, creating a fifth spoke designated

Hall A. On the sides of the central

corridor of the ground floor of this, corresponding to Ward 2 of the other

halls, were situated the rooms where prisoners received visits (under

surveillance) from their relatives and friends, while over it was the

chapel. Underneath the control centre

was the store where the finished products of the prisoners’ work were kept

until despatched. On the same level as

this under Hall A, was the prison kitchen, while the equivalent floors of the

other halls contained the dungeons.

These were cells that were mostly below ground level, some of which had

iron rings attached to the walls for securing the unfortunate prisoners who

were ordered to be kept in irons. The

halls were lettered A, B, C, D and E, rotating in a clockwise direction.

From this description

it will be easily understood that the cells near the hub room were particularly

dark and airless and these conditions were responsible for a number of COs

contracting tuberculosis.

The layout at Wormwood

Scrubs obviated these corner cells, but necessitated a control desk for each

and every hall. Moreover all the cells

were above ground and therefore the equivalent of the Wandsworth dungeons must

have been in a separate building, if they existed at all.

While on this subject,

I must not omit to mention in retrospect, the Wormwood Scrubs Hall A Principal

Warder, a man of the name of Johnson.

This individual was the possessor of a voluminous voice the like of

which I have never heard before or since.

He could fill the vast building with a noise like the roar of a giant,

or a gargantuan loud-speaker and in imagination, I can still hear him bawling

out notice to the officers on the wards above, of the approach of prisoners

belonging to their charge, “Coming up! Twos! Threes! And Fours!” Truly there was no excuse for any of them

being unaware the necessity of locking their men in.

On the following

morning we were taken down to the control centre where the Governor inspected

us. This gentleman, Mr. Percy Greene,

appeared to be a happy-go-lucky, nonchalant sort of person, whose office was a

sinecure, the onus of the duties falling almost entirely on Mr. Walker, the

Chief Warder. Among the COs, the

Governor received the nickname of Micauber.

In my mind’s eye, I can still see him coming across the centre twirling

his keys in his right hand, his left thrust deeply into his trouser pocket, and

his eyes fixed upon the roof, to all appearances perfectly oblivious of his

surroundings. When he reached us, as we

were drawn up in line, he took the records from the guard officer and glancing

at them, he pointed to each of us in turn with one of his keys, and asked,

“Blake? Brownutt? Simons?” and we each replied, “Yes, sir!” Then he handed the papers back to the warder

and asked us one by one if we wished to do any particular kind of work. With my thoughts on my work at Wormwood

Scrubs, I replied that I wished to be free of all work that was intended for

the army or navy. The Governor just

nodded his head and walked off as if did not have a care in the world and left

the officer to make the notes and expedite matters.

After this we were

taken to the cells, which were to be our permanent abode. These were also situated in Hall B. My cell was number 45 in Ward 4, being on

the top floor.

The officer of Ward 4 was a short, elderly man named Butler, and in my opinion he was utterly unfitted to be a prison warder. He was far too humane for such an ethically dirty job and although illiterate, was more of a real gentleman than many wellborn persons. He had quite a fatherly interest in the welfare of his charges and strenuously avoided placing anyone on report if at all possible. If however, he found it unavoidable, I verily believe that it worried and pained him far more than it did the prisoner concerned. I got my first glimpse of him on the morning after our induction into his ward, when he came round with breakfast. As soon as he unlocked my door and saw the uniform I was wearing, he exclaimed, “Ah! You’re second division.” And to my unbounded astonishment, I received a pint of cocoa in addition to the ordinary breakfast. Needless to say, I did not protest, but rather, asked no questions for conscience sake, but the mistake was not repeated on subsequent mornings. Later that morning I discovered that there were only three COs in the prison when we arrived, so we brought the total up to six.

When our cells were opened one morning a few days later, we found that Runham-Brown had joined us, but that he had arrived alone and so when the opportunity presented itself, I asked him surreptitiously what had become of Tinkler. The query brought forth a chuckle of intense amusement and the reply, “Oh! He’s upset his trial.” This answer mystified me considerably, and I further asked, “How?” Runham-Brown then explained that Tinkler in the course of his court-martial had complained to the Court that he had not been allowed to see anyone, not even to consult with his ‘court-martial friend’.

I should explain here that Tinkler had in

his possession, unknown to the authorities, a copy of The King’s Regulations,

which is the complete code of army law and seemed to know it almost inside

out. He had gained from this that a soldier who is to be tried

by court-martial is privileged to select a friend to assist him with his

defence and he MUST be allowed to consult, as circumstances require. The Adjutant’s stringent veto of

communication had rendered such consultation impossible and Tinkler made a

point of it in his trial, with the result that Headquarters quashed the trial

as having been improperly conducted and the regimental officers were put to the

trouble and expense of instituting a new trial for him. This had the effect, besides making him very

wild about it, of causing the Colonel to order the lifting of the veto and when

we subsequently returned to the barracks, we found that there was practically

no restriction on visitors and no restraint on correspondence. Incidentally, Tinkler was frequently

catching out the barracks officers in the infringement of some army regulation

or other, and he became to them a ‘bete noir’ of whom they had a wholesome

dread.

Right at the outset, we

found to our relief, that COs on a second sentence had the first month in

solitary confinement waived and we went into associated labour straight

away. In other respects, we had to

proceed through the stages, up to the fourth stage in the usual way.

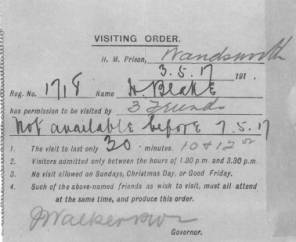

When we had been in Wandsworth Prison about a fortnight, my gentleman officer of the reception department came round our ward with supper one evening. On seeing me when he unlocked my cell door, he engaged in the following short conversation, in contravention of all the prison rules, which direct that an officer must not communicate with a prisoner other than the running of the institution requires. “Hullo! How are you getting on? Does your wife still like you?” “Yes, of course” I replied confidently. “Ah! You never know, even the best of girls turn sometimes.” “I have every confidence in her.” “Good! Well I hope she wont fail you. Good night!” Goodnight!”

The next incident that comes to my mind happened on the occasion of the routine fortnightly searching of our cells. For this purpose the prisoner, after having his person searched for contraband articles, has to stand outside his cell on the landing, while one officer mounts guard over him and another ransacks his cell. On one such occasion, the Senior Officer said to me as he commenced operations, “I just want to make sure you haven’t got any guns or swords up your coat, or any bombs in your pocket.” Afterwards as I stood outside, the other officer chatted to me, “What makes you take this line against the army?” “Because I believe that Christ’s teaching is definitely against the use of violence.” “Do you object to sport, then?” “What do you mean by sport?” I asked, being extremely cautious. “Well, football!” “I’m not particularly enthusiastic over football, but I can’t say I’ve any objection to it.” “What about boxing?” “I don’t see any sport in two fellows knocking one another about.” “But don’t you believe in learning self-defence?” “No! Self-defence as you call it, isn’t permitted to a Christian, so why learn it?” “You don’t believe in it then?” “Decidedly not!” “Well! They’ll keep you in and out of these sort of places for seven years, you know.” “Then the only thing to do, is to stick it out.”

In the evenings, after the nights had begun to get cold, when my cell task was finished, I had been in the habit at Wormwood Scrubs, of getting down the bed board, which in the daytime was stood on end against the wall, with the bed clothes folded strictly in regulation manner and hung over the top-end and sitting on the bedding with my legs covered by the coverlet and my back against the wall. In this manner I managed to keep warm and comfortable while I read and although at that prison they were so strict on the observance of the regulations, no exception was ever taken to this practice. But on almost my first night at Wandsworth, as soon as I had settled down to read, the night officer came round peeping through the ‘Judas hole’ and he demanded to know why I was not at work. I replied that I had finished my task, and he then wanted to know what I was doing. I informed him that I was reading. Then he asked if I was reading in bed and I said that I was sitting on the bed. To this he replied that it looked to him as if I was in bed with my clothes on and he ordered me to put the bed-board against the wall and not get it down until the bell rang. After staying to see me put his order into effect, he passed on. On succeeding nights throughout the winter, I waited until the officer had taken his peep into my cell, and then immediately got down the bed and settled down as before and nobody was ever the wiser.

There was at Wandsworth, within the outer walls of the prison but within its own self-contained section partitioned off by an inside wall, a detention barracks for soldiers. The prisoners were confined to separate cells that were precisely the same as the cells for the civil portion of the prison, but which were called rooms however. They also had to perform the same work tasks, but they retained their army uniforms and spent considerable part of their time in military drill. The number of detention prisoners became so large during the war, that the barracks section was not commodious enough for them and accordingly, Hall C was handed over to the military authorities, and divided off from the civil side of the prison by the erection of a huge wood and canvas partition, at the control centre end. As the number of CO prisoners rapidly increased, it was seen that Hall B would not be large enough to accommodate them. Therefore after I had been in the prison about six weeks, the COs were transferred to Hall C, which was larger than Hall B, which was thereafter used exclusively for army prisoners undergoing hard labour sentences, under which category COs technically came. Hall B was now divided off from the control centre by the wood and canvas partition.

In this re-arrangement, Brownutt, Simons, and myself became finally separated from our Mill Hill comrades, including Runham-Brown who was placed in Ward 2, while we were located in Ward 3. Our benign warder, Mr. Butler, being transferred to take charge of this latter ward. The number of the cell in which I found myself was 33 and with this cell I had a long, very long association. We were also divested of our second division clothing and rehabilitated in the more sombre regulation dark grey as for army prisoners.

As my thoughts dwell in remembrance of this detention barracks, my mind is filled with a totally inexpressible amazement at the stupendous stupidity of the authoritative mind. While endeavouring to coerce COs into military service, how could they commit an astounding blunder of such gigantic magnitude as the immuring of them in a prison where they could see much of the workings of a detention barracks? Surely if there was one thing needed to stiffen their resistance, and incite them to a determination to stand firm in their opposition to the last gasp, this was IT. As I think of the horrors of brutality which were practised on the unfortunate soldiers who found themselves in that place, my whole soul cries out in execration against those who called themselves disciples of Jesus, yet lent their support, under the flimsy and cowardly pretext of expediency, to the forcing of unwilling men into the clutches of the devils, who exercised their diabolical designs upon them in callous cruelty and without redress. Words fail me and I feel, as the costermonger must have felt when he exclaimed, “There ain’t no words bad enough.” Surely, Oh! Surely, Jesus died to save men from the degrading and brutalising influence of such nightmares of horror, by deposing the satanic emissaries who use them, NOT that his name might be used as a lever to force them into these hotbeds of diabolism.

As the year 1917 approached the vernal equinox, the weather set in very cold and on the first day of spring it snowed heavily. The climatic conditions induced a return of my neuralgia and the sight of thickly falling snow, from the workshop windows, constituted for me with the pain I was suffering, a very dismal sight and in an endeavour to somewhat relieve my pent up feelings, I muttered under my breath, “Oh! Confound the weather!” Jones who was working on the same table, upon hearing this responded, “Lloyd George is the man you ought to curse. He is the cause of all your trouble,” and I replied, “We don’t know what problems he has to face and anyway I can’t do the weather much harm if I curse it.”

I traced the cause of my malady to a canine tooth, which had developed a slight defect. In consequence, I asked one morning to see the doctor, for a tooth extraction. However the doctor demurred about this, stating that the tooth was really a good one and that it only wanted the attention of a competent dentist. He therefore gave me a good dose of quinine, so large that it made my ears sing for some time, like a near-boiling kettle. So I took my problem to the Governor. He explained to me that the doctor thought it would be a pity to sacrifice the tooth for the want of a little attention and offered me the privilege of writing a letter to my family, so that I might ask them to make arrangements for a dentist to come into the prison. This suggestion I strenuously opposed, as I had in mind that my wife had financial burden enough without such an addition being put upon her. So I asked the Governor if the doctor could extract it. On this point the Governor would not commit himself and dismissed me with the advice to think it over.

Why the officials were so insistent in saving that tooth, I am at a loss to understand, as I knew that the dispenser in the prison hospital was a good tooth extractor and I do not believe for a moment that they would have made the same difficultly with one of the ordinary prisoners. But shortly after I had returned from my interview with the Governor, I was fetched from my cell and taken to the hospital dispensary, where I was quickly relieved of the troublesome tooth, the dispenser jocularly remarking as he selected the appropriate instrument for the job, “As a CO, I should have thought that you would have objected to the shedding of blood.” Perhaps this remark throws some light on the matter. Very possibly they thought that a CO who would shrink from the inflicting of pain on another, would also shrink from pain to his own person and would therefore be a troublesome patient, without either a general or local anaesthetic. Or in other words, like most small-minded people who could not understand our attitude to war, they thought we were essentially cowards.

Whose Image and Superscription?

The story of a First World War conscientious objector